For most sports fans, the name “Armstead” is synonymous with Arik, a veteran lineman on the monster 49ers defense. For professional basketball players — both in the NBA and across the world — the name immediately conjures 100-degree days and double workouts in Sacramento. That’s where Guss Armstead, one of the most respected basketball trainers in the country, holds court. Guss, who is Arik’s father, hosts his own summer league, preps players of all skill levels, finds players housing and even feeds people on occasion. He’s beloved among pro ballers, not just for his elite training skills but for creating a true support network.

I first met Guss on a hot Sacramento spring day more than 15 years ago, when I walked into “Basketball Town,” Armstead’s longtime headquarters. (It closed in 2007; Armstead’s hub is now at Sacramento’s Sport Courts Fitness.) There were three full-size courts populated by NBA players like Matt Barnes, Bobby Jackson, Andre Miller and Brad Miller. I was there looking for a man I had never seen and therefore looking for anyone who resembled a coach. I never did find that person, but what I did find was a tall, bald, dark-skinned man in a black T-shirt, long black shorts and cross-trainers laughing at people for missing layups. It felt like part gym, part barbershop. I knew I was in the right place. I wasn’t just experiencing the world of offseason basketball training for the first time; I was experiencing a community that had been building for decades.

‘I kind of just fell into it, to be honest’

Guss’ connection to NBA players dates back to the 1980s, when he was a grad assistant at Sacramento State. The Kings moved to Sacramento in 1985, and NBA teams in town were looking for a convenient place to get shots up.

“Mitch Richmond and the guys back in the day when the Kings were first here, I was the guy that when they were going to go play, they were saying, ‘Hey man, meet up at Sac State,’” Guss told me. “I was putting together runs. And then some of my friends started asking me to train them, some of the guys that were in the NBA, and I kind of just fell into it, to be honest.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/arik-armstead-tout-021224-b1e35ff9441a4c0594adf737adfeed0e.jpg)

What started accidentally became an intentional space. You might get dunked on and laughed at, but then someone will drive you home and get you a burrito. Matching up with big names on a daily basis was both fun and terrifying. In my time training with Guss, I was put up in a house, driven to the facility and fed when I was broke. Without that support, I likely wouldn’t have made it as a professional.

“This was a place to come,” he says. “‘If I don’t have an opportunity, I can get with Guss, and Guss has connections with agents and people all over the world to where I can make this a career.’ … There was a healthy environment that was conducive for them to grow in the game, and they would come in and get challenged, too. You come in the gym, and back in those days, JaVale McGee, freaking Andre Miller was in there sometimes.”

Armstead’s approach — challenging young athletes to build skills and offering a community while they do — has led to high praise from alumni. Phil Handy, a Lakers assistant and highly respected skills coach, called Armstead’s training setup “The Lab” that first day I walked in back in 2006.

“We take guys and grow them into players,” Handy told me years ago. When I asked him recently how many guys he believes Guss has gotten to the NBA, he replied, “Hundreds. Countless. I don’t even want to limit it to the NBA because he’s helped players at all levels. He’s the guru and the godfather mixed up.”

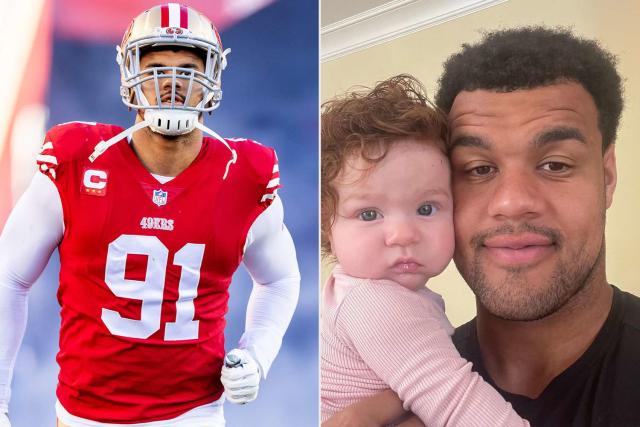

One player Guss didn’t get to the NBA was his own son, Arik, who was recruited to Oregon as a two-sport player and suited up for one game for the Ducks’ basketball team before quitting to focus on football. In a 2020 interview, though, Arik described a game that would make his dad proud. He compared himself to Boris Diaw, saying he was “a skillful big who can shoot a little bit. … I wasn’t high-flying around the rim. I had a skillful game.”